(Publish from Houston Texas USA)

(By: Brig Sadiq Rahi, Sitara E Imtiaz (Military), Retired)

The recent controversy surrounding the article “It Is Over” by Zoran Nizamani has been deliberately inflated into something far larger than it deserves to be. What should have remained a routine editorial decision has instead been framed as an act of censorship, a silencing of youth, and, rather melodramatically, the suppression of a revolutionary manifesto. A closer, more sober examination, however, reveals a far less sensational reality.

Those who worked in print journalism a decade or two ago understand that no article reached publication without passing through multiple editorial filters. Sub-editing, fact-checking, stylistic corrections, and rigorous proofreading were not optional formalities; they were the backbone of credible journalism. Even then, if an error slipped through, newspapers did not hesitate to issue public corrections or apologies. Editorial accountability was a matter of professional pride.

The advent of online editions has not abolished editorial responsibility; it has merely altered its mechanics. Digital platforms allow errors to be corrected instantly, and when a piece is found to be structurally flawed, excessively repetitive, or inadequately edited, it is neither unusual nor conspiratorial for an editorial desk to quietly remove it. This happens daily across reputable international publications and is generally understood as an editorial correction, not a political intervention.

Against this backdrop, the deletion of “It Is Over” hardly qualifies as an extraordinary event. The article did not name specific individuals, did not explicitly target any institution, and was no harsher in tone than dozens of opinion pieces published daily in Pakistan’s press and on social media. It is therefore difficult to argue, in good faith, that some unseen hand urgently moved to suppress it out of fear or insecurity.

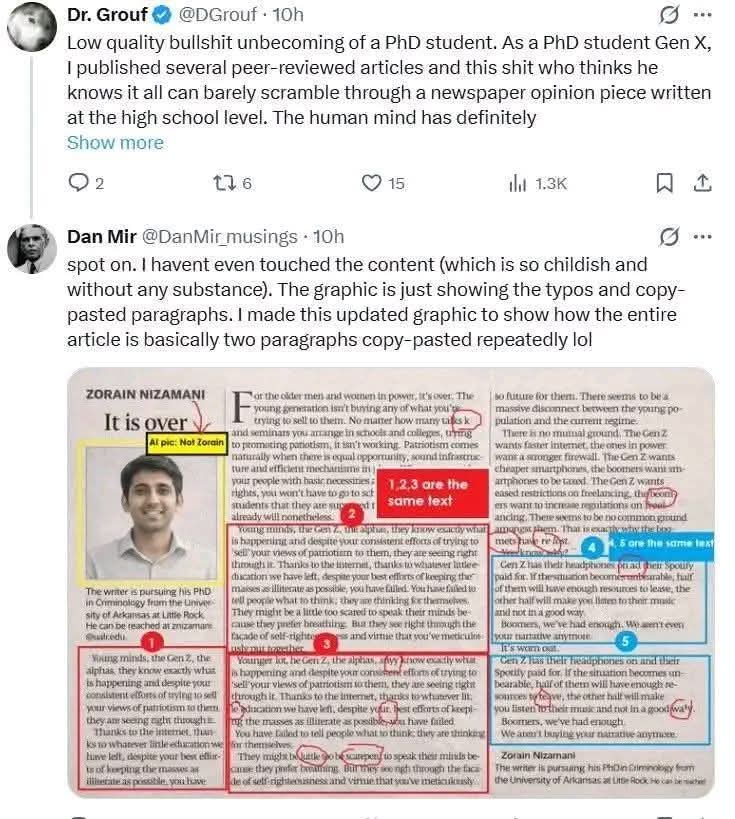

What makes the editorial decision more comprehensible is the article itself. A careful reading of the published version, screenshots of which continue to circulate, reveals a troubling lack of editorial polish. Entire sentences and paragraphs are repeated almost verbatim, arguments circle back on themselves without development, and basic proofreading errors remain unaddressed. Such lapses are not matters of ideological disagreement; they are issues of journalistic competence. For an opinion piece presented as a generational diagnosis and authored by an academic affiliated with a foreign university, these flaws are particularly glaring.

It is therefore far more plausible that the publication chose removal over revision simply because re-editing the piece would have required substantial restructuring. In editorial terms, this is a practical decision, not a political one.

Yet a segment of social media commentary has chosen to mythologize the incident. According to this narrative, had the article not been removed, Pakistan would have been on the brink of an uprising by Friday evening. The exaggeration is almost theatrical. It reflects the same impulsive thinking that repeatedly assumes dramatic political reversals are always just forty-eight hours away, contingent only upon the right slogan, speech, or viral post.

Revolutions, however, do not emerge from poorly edited opinion columns, nor do states unravel because of repetitive prose and rhetorical flourish. Pakistan is a country of over 240 million people, with a literacy rate hovering around sixty percent and an English reading elite comprising barely a fraction of the population. To suggest that a single English language column or an opinion is flawed in structure and limited in reach;

To catalyze a nationwide upheaval is to profoundly misunderstand both society and history.

What is more concerning is the tendency to transform every editorial or professional shortcoming into a narrative of oppression. When weak writing is recast as suppressed truth, and editorial discretion is framed as authoritarian fear, the result is not the strengthening of free expression but its trivialization. Journalism suffers when standards are lowered in the name of victimhood, and public discourse deteriorates when technical criticism is dismissed as ideological hostility.

None of this is an argument against dissent, critique, or generational questioning. A society progresses through debate, disagreement, and self-reflection. But critique gains legitimacy only when it is rigorous, well-argued, and competently presented. To conflate poor editorial quality with political persecution is not resistance; it is evasion.

The real issue, therefore, is not that a bold truth was silenced, but that journalistic rigor was absent. States are not shaken by careless columns, nor are institutions undone by repetitive arguments. If the intention is to speak for a generation, the responsibility to meet basic standards of clarity, coherence, and professionalism becomes even greater.

“It is over,” then, is not an accurate description of Pakistan’s political reality. At most, what ended quietly was the online life of a weakly edited article, an unremarkable editorial correction elevated into false martyrdom. The lesson to be drawn is not about censorship or collapse, but about the enduring necessity of seriousness in writing, especially when one claims to speak for millions.

About the Author:

Conferred with Sitara-e-Imtiaz (Military), the author is a retired senior officer of the Pakistan Army with more than 35 years of experience in governance, security, logistics, administration, and institutional leadership. He has served in United Nations missions, represented Pakistan at international forums, and held senior appointments in both military and civilian organizations, including national infrastructure and financial institutions. He is currently a visiting faculty member at the National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST). His work focuses on governance reform, transparency, public-sector modernization, and national security policy