(Publish from Houston Texas USA)

(By: Brig Sadiq Rahi, Sitara E Imtiaz Military, Retired)a

Introduction

Across Pakistan, thousands of school and college students, many below the legal driving age؛ are compelled by circumstances to ride motorcycles daily. While the law prohibits issuing a driving licence to anyone under 18 and rightly emphasises road safety, the ground realities in countless middle- and lower-income households create a dilemma. For many young boys, riding a motorbike is not a matter of thrill-seeking but a socio-economic necessity: reaching distant schools, transporting younger siblings, compensating for the absence of adult family members, or avoiding unaffordable transport costs.

The recent implementation of traffic rule enforcement and fines by the Punjab government has brought this issue to the forefront. While enforcement is essential for reducing road accidents, the current punitive model—challans, heavy fines, and in some cases FIRs—has begun to create serious long-term consequences for minors, many of whom are already burdened by economic stresses. This calls for a sensible balance between safety, law enforcement, and social realities.

Government’s Recent Announcement on Traffic Violations and Fines

The Punjab government recently directed stricter enforcement of traffic laws against underage driving, including:

⦁ Immediate ticketing/challan of under-18 riders

⦁ Impoundment of motorcycles

⦁ Heavy fines

⦁ Possible FIRs on repeated violations

⦁ Emphasis on helmet and licence requirements

These measures aim to improve road safety, but the absence of a parallel social policy framework places vulnerable student riders and their families at risk.

A Critical Scenario: Why Students Are Forced to Ride Motorbikes

For many households in Punjab, the enforcement narrative overlooks the socio-economic pressures that force minors to ride motorcycles:

⦁ Lack of adult family members

Single-parent households, labour-class families, or homes where adults leave early for daily-wage jobs often rely on the eldest child (even if under 18) to manage school drops and pickups.

⦁ Economic constraints

A significant segment of the population cannot afford:

⦁ School vans

⦁ Rickshaw fares

⦁ App-based transport

⦁ Bus timings that do not align with school schedules

For these students, a motorbike is not a luxury—it is the only viable option.

⦁ Cultural and safety considerations

In many areas, families hesitate to allow girls to use public transport due to safety concerns. As a result, younger brothers often escort their sisters to school.

⦁ Rural and peri-urban realities

In villages and small towns, schools and colleges are often miles away without any formal transport systems. Motorcycles become unavoidable. Hence, while the law is black and white, the lived reality of families is not. The current enforcement approach punishes those who are already struggling.

Consequences of Fines, Challans, and FIRs on Students

⦁ Psychological Impact

A challan or FIR can be deeply distressing for a young student. It creates:

⦁ Anxiety

⦁ Fear of traffic police

⦁ Shame within the family and community

⦁ Loss of confidence

For a child, this can be traumatic and distracting from studies.

⦁ Economic Impact on Families

Heavy fines strain low-income families

Impounded motorbikes disrupt daily life and work routines

Repeated challans multiply financial pressure

In many cases, the bike is the only means of mobility for the household.

⦁ Criminal Record and Future Employment

This is the most serious concern. Even a minor FIR, especially in digital police and Nadra-linked systems, can appear in background checks for:

⦁ Government jobs

⦁ Armed forces

⦁ Police

⦁ Corporate sector

⦁ Overseas employment

A teenager who receives a record for a traffic-related issue may permanently damage his future career prospects. Punishing a child for circumstances beyond his control risks creating a cycle of disadvantage.

⦁ Educational Disruption

When a bike is impounded, or challans accumulate:

⦁ Students miss classes

⦁ They cannot reach schools and colleges in time

⦁ Some may discontinue education due to transport barriers

Ironically, a policy meant to promote safety may unintentionally contribute to school dropouts.

Recommendations

To balance enforcement with social justice, the following policy recommendations are crucial:

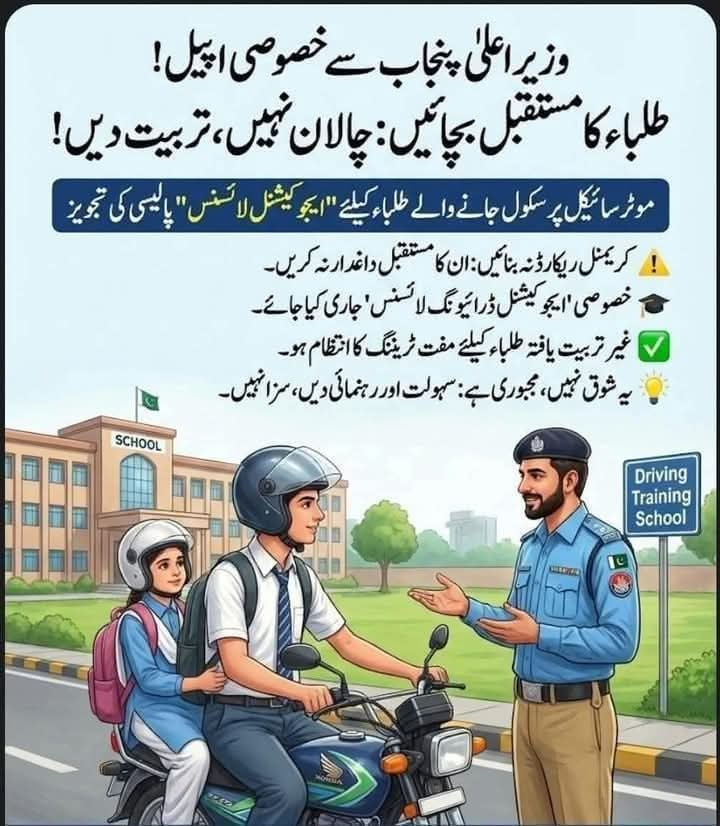

⦁ Introduce a “Special Educational Commuter Permit” for 16–18-year-olds

⦁ Conditional, limited-permission permit

⦁ Mandatory helmet

⦁ Mandatory parental consent

⦁ Speed restrictions

⦁ Only for travelling to educational institutions

Several countries offer such controlled permits to ensure safety without criminalising minors.

⦁ Replace FIRs with “Non-Criminal Traffic Counselling Notices”

⦁ No criminal record

⦁ Mandatory road-safety awareness class

⦁ Community service at schools

⦁ Warning slips, not FIRs

⦁ Parental Accountability System

⦁ Instead of punishing the student:

⦁ Fines should be issued to parents/guardians

⦁ Parents must attend one safety seminar

This shifts responsibility without ruining a student’s future.

⦁ Improve School Transport Infrastructure

Government and district administrations should promote:

⦁ Affordable school van programs

⦁ Subsidised transport for low-income families

⦁ Public-private partnerships for safe student mobility

⦁ Community-based Road Safety Education

Schools should integrate:

⦁ Helmet campaigns

⦁ Road safety training

⦁ Peer awareness programs

This will reduce accidents without criminalisation.

Conclusion

Strict enforcement of traffic laws is important, but laws must account for socio-economic realities. When a minor rides a motorcycle, it is often not out of thrill or defiance—but necessity. Imposing fines, impounding bikes, or filing FIRs against such children risks harming their education, mental health, and long-term career prospects. A child who is forced to help his family should not be turned into a criminal by the system. A more compassionate, balanced, and policy-driven approach is essential—one that promotes road safety while safeguarding the futures of Pakistan’s youth. The government must consider creating special educational permits, parental accountability systems, and affordable school transport solutions so that road safety enforcement does not become a source of long-term injustice.

Author biography

Brigadier (Retd) Sadiq Rahi, SI(M), is a graduate of the National Defence University, Islamabad, Command and Staff College, Quetta, and the Command and Staff College, Cairo (Egypt). Over a distinguished 31-year military career, he held key command, staff, and instructional appointments. He also served as a Platoon Commander at the Pakistan Military Academy, Kakul, and as a Staff Officer (Logistics) with the United Nations Peacekeeping Mission in Somalia.

Brigadier Rahi represented Pakistan at eight international conferences under the auspices of the United Nations Office in Geneva, where he presented Pakistan’s national standards and protocols. He has also served as a guest speaker at the National University of Science and Technology (NUST), Islamabad, delivering lectures on UN and International Logistics.

Beyond his military and professional contributions, Brigadier Rahi is widely recognized as a poet and writer. His poetry, ghazals, and prose have been published in national newspapers and literary journals since his student days. He served as Editor of the college magazine Nakhlistan and later as Editor of the Pakistan Military Academy magazine Qiyadat. Presently, his columns appear regularly in Nawa-i-Waqt, The Nation, Pakistan Chronicle, Houston USA. He continues to write actively both in Urdu and English, maintaining a strong presence on social media as well.